NASA’s Heliophysics Experiment to Study Sun on European Mission

Www.oeisdigitalinvestigator.com:

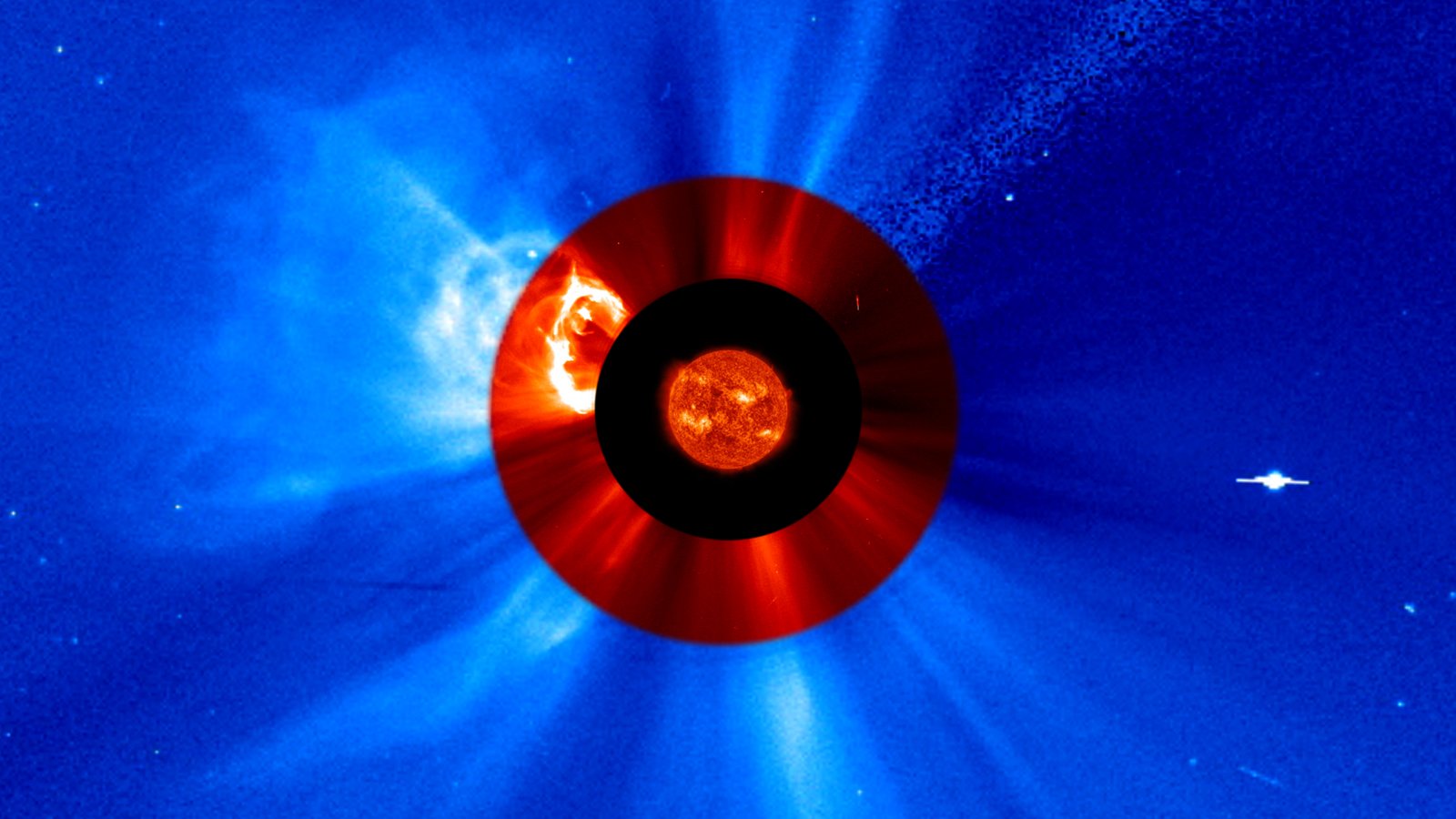

NASA announced Tuesday it selected a new instrument to study the Sun and how it creates massive solar eruptions. The agency’s Joint EUV coronal Diagnostic Investigation, or JEDI, will capture images of the Sun in extreme ultraviolet light, a type of light invisible to our eyes but reveals many of the underlying mechanisms of the Sun’s activity.

Once integrated aboard the ESA’s (European Space Agency’s) Vigil space weather mission, JEDI’s two telescopes will focus on the middle layer of the solar corona, a region of the Sun’s atmosphere that plays a key role in creating the solar wind and the solar eruptions that cause space weather.

The Vigil space mission, planned to launch in 2031, is expected to provide around-the-clock space weather data from a unique position at Sun-Earth Lagrange point 5 – a gravitationally stable point about 60 degrees behind Earth in its orbit. This vantage point will give space weather researchers and forecasters a new angle to study the Sun and its eruptions. NASA’s JEDI will be the first instrument to provide a constant view of the Sun from this perspective in extreme ultraviolet light – giving scientists a trove of new data for research, while simultaneously supporting Vigil’s ability to monitor space weather.

“JEDI’s observations will help us link the features we see on the Sun’s surface with what we measure in the solar atmosphere, the corona,” said Nicola Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Combined with Vigil’s first-of-its-kind, eagle eye view of the Sun, this will change the way we understand the Sun’s drivers of space weather – which in turn can lead to improved warnings to mitigate space weather effects on satellites and humans in space as well as on Earth.”

The project is led by Don Hassler at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. The instrument is funded by the NASA Heliophysics Space Weather Program with a total cost not to exceed $45 million. Management oversight will be provided by the Living With a Star Program of the Explorers & Heliophysics Projects Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

For more information on NASA heliophysics missions, visit:

https://science.nasa.gov/heliophysics

-end-

Karen Fox

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1600

karen.fox@nasa.gov

Sarah Frazier

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

202-853-7191

sarah.frazier@nasa.gov